This is sketch material relating to options we might consider for protecting our selves and our relationships from the deleterious effects of the increasingly difficult interpersonal climate pervasive in highly modern societies like ours.

In essence, each recommendation is meant as a contribution toward a kind of “sociotherapy”, a program of suggestions designed to bolster our defenses at the personal level against one or another of the major dimensions of change discussed in my book that have tended to erode security of being and increase psycho-emotional distress.

I welcome your feedback, examples, and suggestions.

Hierarchical to egalitarian

Of course, while it can make issues of self more complicated, the movement from societies in which social standing is founded in hierarchy to modern egalitarianism is highly welcome on moral grounds. In hierarchical societies, people born into a particular social status obtain a fixed identity at birth, and so spend less time questioning who they are, or wondering it they’ve tried hard enough to be all they can, or suffering the blows to self that come from failed ambition (I could have been a great ____ if I’d just tried harder, etc.). In egalitarian societies, continually working to attain social position (rather than just being born into it) is difficult, made much harder by the commonly held misconception of our times that we are each equally capable of attaining whatever life outcomes we strive for, a cruel belief that makes it impossible to avoid the conclusion that our failures of ambition result from our personal inadequacy. Regardless of all the damage done by this trap, on moral grounds, there is no question that everyone should be given the chance to become the best version of themselves. The long-fought movement to egalitarianism has meant personal liberation for countless members of minority groups. No suggestion here to return to former times characterized by societal hierarchies that institutionalized misogyny, racism, homophobia, religious chauvinism, and xenophobia.

However, many hierarchies are open to anyone and are based in merit, and they should be preserved and protected. Finding one’s place in them, even at a subordinate level, can be helpful to the self concept as long as it is clear that hierarchical achievement is available to all, and is legitimately merit-based (not based on where you live, how you speak, the resources provided at birth, etc.). In hierarchies that are not legitimately merit-based, everyone suffers. As one example, the dramatic grade inflation that has occurred in universities during the last few decades has certainly done more harm than good to students’ sense of self. What does it matter if you are an above average student if everyone is an above average student? No one feels good about working in an organization where people rise on the basis of corrupt behavior or personal connection. No athlete feels good about winning when it is apparent that the judging is rigged or it’s known that others are cheating with performance enhancing drugs. Honest hierarchies create opportunities to grow strong selves while dishonest ones undermine us.

It has often been suggested that a major component of self esteem — our feelings of satisfaction about who we are — reduces to a question of how often we succeed at the things we aspire to accomplish. We need opportunities for accomplishment: big goals or little ones, the size doesn’t much matter. We just need to challenge ourselves and watch ourselves succeed. The baselines we use to measure our accomplishment may be internal, meaning that we are competing not against others in an external hierarchy, but against our own previous performance. Still, often the measure of success will be external. Equal opportunity in merit-based hierarchies can provide that.

Participating in teams or helping others to accomplish their goals can also strengthen foundations of self — we don’t have to do this alone. In fact, the better we are at resisting the isolating tendencies of modernity, the more likely we are to invest in others, growing a sense of communal accomplishment and reaping the rewards for identity that inhere in cooperative striving and collective identity. It may be difficult for people in highly modern societies to reorient to collective action and a communal sense of being. It may be equally difficult for those in non-modern societies to imagine otherwise, living as we moderns do, as isolated individuals in competition with everyone around us.

Tradition centered to individual centered

Tradition reduces the significant psychological overhead associated with the need to make all choices fresh in the present. Tradition reflects the collective wisdom about how to accomplish what we want. In its absence in modern societies, people confront their future without guidance, needing to make every decision anew. To push back against this, promote personal or family traditions. Find things that work, and stick with them. Populate the calendar with activities that celebrate social relationships and values (birthdays, doing environmentally helpful activities on Earth Day, doing something to celebrate your marriage or your friendships on a certain regular schedule). Don’t shun the old just because something new has come along (landline phones have clearer signals and protect from incessant interruption, vinyl records and large speakers sound better than MP3s streaming into smart speakers or ear buds, reading nonfiction books is a superior method to gaining exposure to new ideas and reading fiction books is dramatically more psychologically involving than watching a story on the screen, texting is an interpersonal disaster, etc.). In other words, take a critical stance toward the new. New technologies often carry along unintentional consequences that can be disruptive of patterns of life that are important to our sense of being, individual growth, and social connections. When the telephone was introduced it was thought it would make it easier for families to remain in contact when members were away, but it also made it much easier for family members to contemplate moving away. Remember the days when the Internet was going to usher in a new era of utopian democracy?

Local to mass culture

The highly visible re-emergence of nationalist political movements in many modern societies (Brexit, Wexit, MAGA/Tea Party, border walls, and similar phenomena in other countries) has been fueled in reaction to globalization. Globalization has had many positive economic impacts, and, until recently, greatly increased global security — countries whose economies are heavily interdependent are less likely to go to war with each other. But against these positives stands the problem of the loss of one’s ability to ground self identity in the unique attributes/values/traditions/stories of their local experience. Today one American town is hard to distinguish from another. Local hotels, restaurants, and shops have often been replaced by national chains and franchise operations, offering identical experiences no matter where you are. Cities like Pittsburgh, Youngstown, and Cleveland, once identified strongly with the steel industry, but that industry left long ago. Gloversville New York was once a world center for the manufacture of gloves, Oneida New York was once synonymous with elegant cutlery, Rochester with Kodak and photographic technology, Troy New York with shirt manufacture. Not any more. Now many towns struggle to brand themselves in hope of regaining some sense there is something unique about them, something that might appeal to people’s sense of personal identification so that they might be more likely to decide to stay put and invest. The data related to urbanization suggests that this is largely a losing battle.

The loss of the local removes anchors for self identity that are related to place. This loss may be reflected in the appeal of nationalist political movements to those in economically distressed rural areas. Being a person from Gloversville New York may not do much to confer identity any more, but seeing oneself as an American, rather than a world citizen, may help. Yet this dynamic may encourage international confrontation instead of international cooperation, which is increasingly vital to solving global problems like pandemics, climate change, and trade inequities.

Perhaps what might be helpful would be a renewed commitment to national and local service. Many societies require a period of national service (not just in the military) for all citizens. This can take many forms and pay off with a culture characterized by a greater sense of common purpose and value, with corresponding benefits for the strength of citizens’ sense of self.

Rural to Urban

Those who live in small rural communities may wistfully contemplate the freedom and possibilities of life in cities (cutely illustrated in the Disney film Zootopia — see the Film tab). Just as frequently, those living in cities dream of escaping the isolating qualities of urban experience to the sense of community that we associate in imagination with rural and small town life. Clearly, even though it may mean limiting self expression, people do better with strong involvement in community (let me be clear that here I am not talking about “gated communities”, which are anything but communal). But most of us live in densely populated areas and we need to deal with that. If you are in the city, recognize that that has particular psychological stresses and actively plan to compensate, perhaps though joining groups that require periodic face-to-face participation with others. Community means shared experiences, shared history and memory, and some limitation to the expression of self. This confers security and helps shore up our minds against the erosion of meaning that accompanies social isolation and high speed information flows.

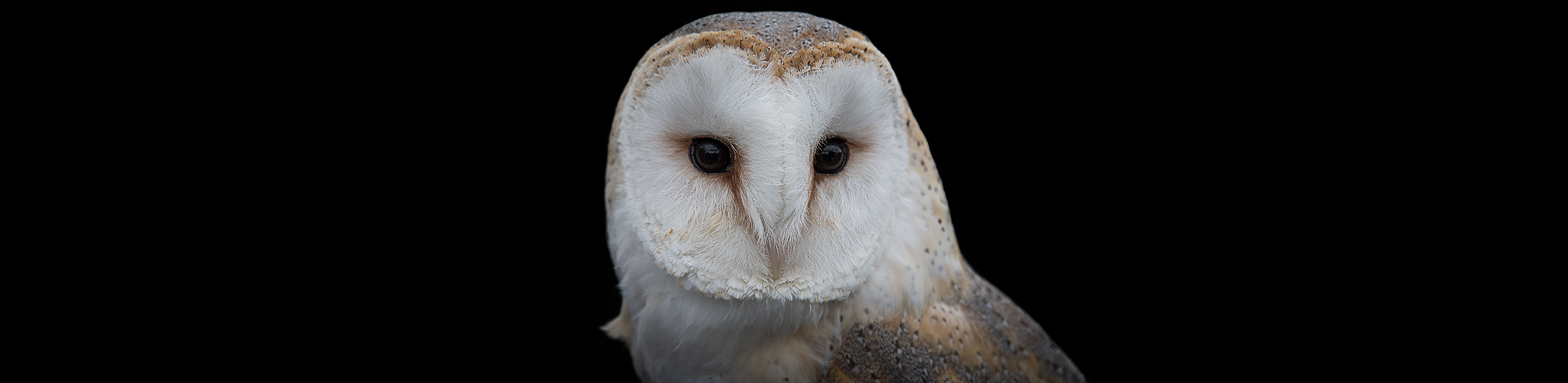

Another major difference between rural and urban life is reflected in relationship to the natural world. There are few people who don’t respond positively to close contact with nature, but this can be difficult in cities, where skyscrapers obscure the sky, the stars, and the sun, and there are few plants, animals, or natural landscapes. Those with different resources will combat the problem of being separated from nature in different ways, but the bottom line is that we are creatures of the natural world and contact with it is always a good idea for at least two reasons: (1) it simplifies the stimuli we need to deal with (for example, an uninterrupted ocean horizon), and (2) because it places us in a context free of uncertainty — there is no idea of the negative in the natural world, things just are (you can never look at a tree and think, maybe its a tree and maybe it isn’t — maybe it just needs me to treat it as a tree, etc., but one very often looks at people with this type of thought process). I recently learned of people referring to hikes in the woods as “forest bathing”. I like this. Regular exposure to nature helps rinse away the erosive psychological soot of city life.

I’m fond of New York City. For ten years I traveled regularly to uptown Manhattan to study music. The city is teeming with creativity and possibility. I always found it exciting. But, of course, I rarely stayed in New York for more than 8 hours. The trouble is that the pace of experience in megacities. is stressful and so New York is also teeming with psychotherapists, mindfulness classes, yoga studies, and bars — places to go to turn down the sensorial load. We need to recognize the importance of managing cognitive load. On the cosmic scale of time, Homo sapiens acquired language very recently — a mere 70,000 years back along a timeline that stretches 14 billion years. And for most of our 70,000 years of language the stimulus load was minuscule. Suddenly, mostly in the last 150 years, the volume of information we process second-to-second has skyrocketed. Imagine walking through Times Square and trying to attend to every sound, or sign, or spoken word that you perceive. We don’t, of course, because, relying on our vision of self, we radically filter, ignoring most, saving our attention for only that which seems relevant to our purpose and goals. Yet, even for someone with this type of well developed sense of self, the continuous stress of this can be overwhelming (for visualization of this, I recommend the film Koyaanisqatsi — see the Film tab).

The mind without language is a quiet place where awareness is always centered in the unfolding present moment. Without language our conscious awareness can only be in the moment, for it is language that creates the abstraction of time and the ideas of past and future. Without language, we can only just be. In all the thousands of years of human experience before language, people could not worry about future outcomes or dwell over past failures. They could not imagine themselves achieving great things or failing to achieve great things. They had no capacity to worry over how others viewed them. They never thought about the value of their own existence. They had no capacity for depression or anxiety. Language is the most powerful invention in all history, but being a language user can be challenging, and especially so in the context of dense urban life where we are continually presented with others to wonder about, and against whom we compare ourselves, and with whom we have to navigate intensely complicated situations. It is easy to burn out in this, which is why retreat to quieter places and developing meditative practices that allow our minds to return to the more natural condition of being-in-the-moment, where it is possible for stress to dissipate. So, meditate, use whatever other practices you enjoy to quiet the mind’s endless stream of talk: lose yourself in dance, or music, or athletic activity. Various sources suggest a strong benefit to those who keep a diary, perhaps because it allows the stream of thought to pour out onto paper, where it can take up new residence.

Public to Private

This dimension is also reflected in the rural to urban shift. Life in small towns and rural areas is much more public, making it a little more difficult to indulge some quirky aspects of self, but also making it more difficult to find oneself isolated. Walk through Manhattan and you may be briefly in view to thousands of people. But this exposure is anonymous and because of this it may actually feed a sense of being cut off from others. Walk through a small town and perhaps you are observed by no more than a few people, but they are likely to know you are local and remember you. The perception of this may lead to feelings of belonging, but also to feelings of being surveilled, unable to express self as you wish for fear of gaining a negative reputation among your neighbors. Because such a large proportion of the population of modern societies now live in cities, the more common problem is the type of isolation that that encourages, exacerbated by the proliferation of communication technologies that encourage withdrawal into the self, like ear buds and cell phones. Privacy nurtures the emergence of self as unique, but there is psychological risk in being overly withdrawn. Balance is essential.

Scholars concerned with modernity’s impacts have often discussed the phenomena of sociological and psychological ‘segmentation’ which is another of modernity’s hallmarks.

Integrated to Segmented

For the majority of human history, from the standpoint of social interaction, people’s lives were considerably simpler. A person might be born into a career situation without choice or opportunity for change. A baker, likely born the son of a baker, would spend his childhood helping his father in the family bakery and one day take it over. Most of his social interactions would be with people in terms of that role position, which was centered in the bakery among the family members, customers, and apprentices who comprised the organization. There was little opportunity for anything else Life was fixed in an immutable groove.

To people in modern societies, who follow a credo of self actualization (finding your inner guiding star, questing for the true self, being all you can be, etc.) the baker’s life sounds restrictive and undesirable. Shouldn’t everyone have freedom to choose and to pursue opportunities for connection and growth across the broadest spectrum of occupations and contexts? After all, as a modern, my sense of self is comprised of a complex collection of sub-identities, each crafted around some ambition of mine that I fancy: I’m a university guy with sub-identities as a research, a teacher, a scholar, and a writer; and I’m also a musician with sub-identities as a flutist, a cellist, a guitarist, and an ethnic drummer; and I’m also head of a technology organization, where I wear a manager’s hat, and work as a software engineer and designer; and I’m also a sports guy with sub-identities as a wilderness kayaker, a cross-country skier, and a figure skater; and I occupy positions in a range of social networks and family structures. And these are just the identities that I’m willing to talk about publicly 🙂 Most likely, I live alone, as is now the case for a majority in modern societies. .

In the circumstances of the baker of by-gone times, it would be idiotic to question his sense of identity. It was dropped upon him at birth, supported by every aspect of his life, and by a majority of is social interactions, and was almost impossible to alter. In the case of moderns with complicated identity structures and highly segmented lives, doubt about the legitimacy of self identity has endless opportunity to leak in (how good of a teacher am I really, since I have so many other things to do and am spread out over so many pleasures and ambitions? — how good am I as a musician since I am spread out over so many pleasures and ambitions? — how legitimate is my claim that I am a good husband/father when my broad and complex social involvements include moral commitments to a typical modern person’s expanse of local and distant relationships? Is it a wonder that modern people are (1) witnessing a culture-level withdrawal from long-term committed intimacy, (2) increasingly reporting that they suffer from loneliness and isolation (3) grabbing prescriptions for anti-anxiety and anti-depression drugs at rates that stagger the imagination (in 2016 594 million prescriptions were written in the United States for just the top 25 psychiatric drugs, a new script for the leading anti-anxiety drug Xanax was written at a rate of one every second of every day and night, 1 in 10 Americans had a script for an anti-depression drug, with the rate at 1 in 4 middle age women)?

Identity is not something anyone forges on their own: it is an outcome of social interaction, requiring continuous re-confirmation and support from others. Can I say I’m a teacher if my students don’t show up for class and apparently aren’t learning anything? Can I say I’m a good flutist if no one wants to listen to me? Can I say I am a good husband if my wife disagrees? Can I say I’m a handsome man and a great partner if I can’t get a date with anyone? Identity is inherently social, and so, paradoxically, in modern societies where people have complicated and elaborate structures of self, we find them withdrawing from other in order to protect what they can of their sense of who they are. I am the most confident of myself as a teacher during my year away from teaching while I’m on sabbatical. I’m most confident of my image of myself as a figure skater when I’m away from the ice. But then, if that withdrawal is protracted, I find anxiety, doubt, and loneliness.

So what can we do? First, recognize that the problem is social and so the solution must be social as well. By themselves mood altering psychiatric drugs solve nothing and contribute to the exasperatingly ungrounded idea that the great malaise of modernity is due to some epidemic level of chemical imbalance in our brains that has just suddenly popped up in recent years. I very much like the suggestion summarized by New York journalist Christina Caron that those who find themselves drifting away from social contact consider volunteering. The best idea is to simplify our ambitions of self and shore up our identities in regular interaction with others.

More to come …